Ticked off: Cracking the code for a cattle tick vaccine ABC Landline: 26 July 2020

They may be small, but ticks are a huge expense for the cattle industry. The parasite causes loss of condition to the animal, illness and sometimes death. A Queensland scientist has spent 15 years trying to crack the code for a vaccine and early results are promising.

TRANSCRIPT - Ticked Off: Cracking the code for a cattle tick vaccine

Landline presenter: Pip Courtney, ABC TV Landline

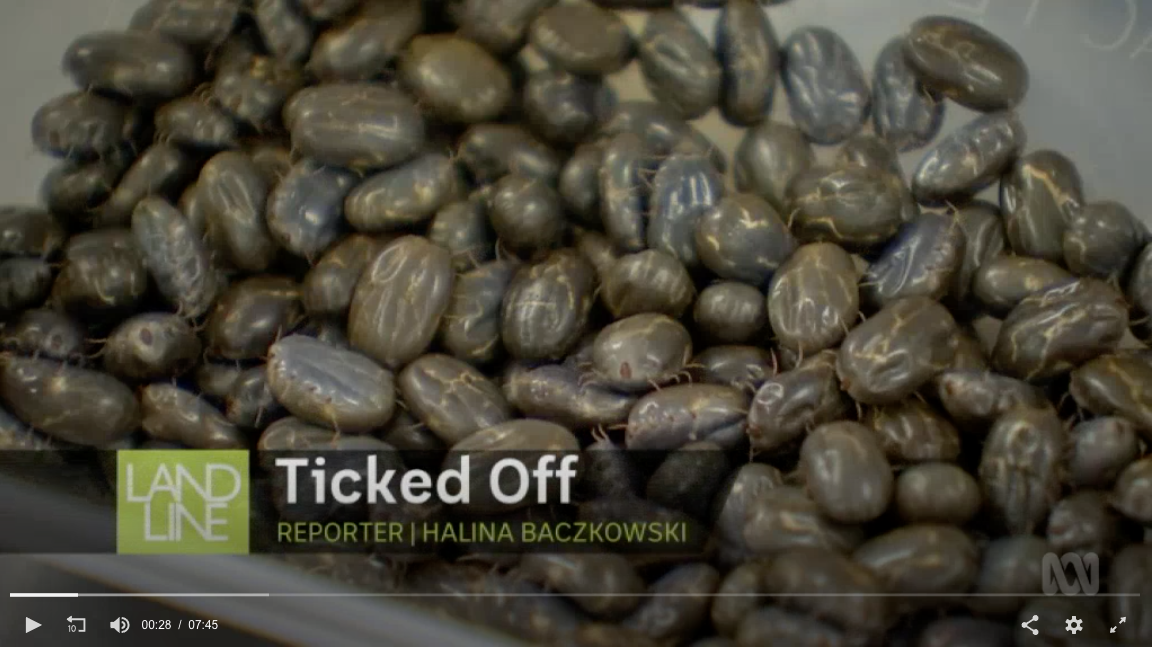

Another big cost to the cattle industry are ticks. Small and sometimes deadly, controlling them costs millions. Landline Halina Baczkowski met a scientist who, for 15 years, has been working on a vaccine, and early results are promising. And if you don't like creepy crawlies, you might want to look away.

Landline reporter: Halina Baczkowski, ABC TV Landline

These are cattle ticks. While you don't normally see them in a tub like this, all of these came off one steer. They're the test ticks in a vaccine trial to manage them.

Interviewee 1: Prof Ala Tabor, Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation UQ:

You incubated them yesterday? So how many animals did you sample yesterday?

UQ QAAFI research assistant: 15.

Ala Tabor:

And did you get lots of ticks from all the groups?

Research assistant:

No, some were a bit lower.

Ala Tabor: Okay, good.

Halina Baczkowski:

These ticks live exclusively on cattle. They can cause a blood loss, transmit tick fever, which causes lethargy and a loss of appetite. And in some cases, death. Professor Ala Tabor is heading the research at QAAFI at the University of Queensland.

Ala Tabor:

The cattle tick are sort of unique that they just stay on cattle for the whole life cycle and it goes for about 21 days. But other tick's going to have a life cycle of a whole year, like paralysis tick in Australia, that's a whole year. Are you ready to mix up the vaccine? Yeah, let's do it.

Halina Baczkowski:

She's been working on a vaccine for years and is hoping this one will yield good results.

Ala Tabor:

So this is mixing up several doses of A vaccine that we're testing soon. So they'll all be mixed up. And this takes about three hours, this particular mix.

Halina Baczkowski:

And I know that you've been working on this research for a long time. How long has it taken to get to this point?

Ala Tabor:

This final trial, it's taken us 15 years.

Halina Baczkowski:

Were you counting?

Ala Tabor:

Yeah, I had to count because every year there's another year goes by. And I'd have to add another year to that year. Probably the last 10 years has mainly been trial work with testing mixtures and going ... narrowing down of our final candidates.

Halina Baczkowski:

With tests still in the early stages, industry bodies like Meat and Livestock Australia will wait until there's a solid result before getting too excited.

Interviewee 2: Jason Strong, Managing Director, Meat and Livestock Australia:

We are involved in tick research and we have been for quite a long time and it's a real challenging one to crack. And while there's been a number of studies over time, there's been a number of really good potential options and particularly on the vaccine front, we're yet to crack that solution.

Halina Baczkowski:

Jason Strong says ticks are a huge expense to the cattle industry.

Jason Strong:

In the North particularly they're a big problem, but even more broadly. And they've been a big problem for a long time. And there's been a number of studies done on the impact of cattle ticks on the industry and there are different numbers, but it's around about $146 million worth of impact on-farm.

Halina Baczkowski:

In the warm climate at Calliope near Biloela in central Queensland, Will Wilson says it's easy to keep ticks under control at the moment, but he can't get complacent.

Interviewee 3: Will Wilson Agforce:

To eradicate is a really big issue. An old person said to me once, the more you think you know about these things, the less you actually do because they turn up when you least expect.

Halina Baczkowski:

For him, the biggest concern regarding ticks is weight loss.

Will Wilson:

I think 10%, without a doubt on animals that are getting infected, but just animals caring, I'd say to be two to five kilos a year on an animal just generally carrying an average population of ticks.

Halina Baczkowski:

80% of cattle subtropical and tropical areas of the world are susceptible to ticks.

Interviewee 2: Jason Strong:

So firstly, there's an inconvenience and disruption and restriction to movement. So there are significant and specific controls in place around trying to control the movement of ticks. So that's a real challenge from a logistical point of view, but on-farm, it's very much a production impact. So it's a reduction in production, it's if they get tick fever or red water, for example, then they obviously get lethargic and die. So, which is obviously a big challenge, but it's really a management challenge. It's a logistical challenge and it's a big cost impost on production in Northern Australia.

Halina Baczkowski:

Will Wilson would like to see more done on tick research.

Interviewee 3: Will Wilson:

I think you need some pretty determined scientists, that'll work for very little.

Halina Baczkowski:

Lab work has been extensive and now professor Ala Tabor and her team are finding out if it's all been worth it. They're administering the vaccine, putting ticks on bulls or in this case steers and seeing if it works. Professor Tabor is testing her vaccine on steers at the University of Queensland's Gatton facility, an hour West of Brisbane. Originally from New South Wales, they've been acclimatised for a couple of months to make sure they're disease-free. And then how long is the trial?

Interviewee 1: Prof Ala Tabor, Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation UQ:

Around nine months long. So we've got them in two different groups, just for ease of managing this group's small, so it's 12, the other group's 24. So there's 36 all up and we vaccinate them. They're all randomly numbered. There are six different groups of six and there are one control group and five different vaccine formulations that we're testing at the moment.

Halina Baczkowski:

Once the trial steers are injected with the vaccine, the ticks are introduced to see how they behave. They're then gathered and cleaned. It's a gross job, but as the saying goes, someone has to do it.

Ala Tabor:

How's it looking today?

Research speaker:

It looks good.

Good.

Ala Tabor:

This one's consistently had a lot less ticks compared to the other ones, hey?

Research speaker:

Yeah, I know. There's definitely some of them that have got heaves.

Ala Tabor:

And the tick guard vaccinated cattle, all the ticks are all red.

Research speaker:

It's that?

Ala Tabor:

Yeah, the one that’s gone all red, but there's still a lot of ticks sometimes. But this is a good result.

Research speaker:

That's a good result?

Ala Tabor:

Yeah. And they're very clean too. You're really good at this.

Research speaker:

Oh, that's good. I love it. I love keeping them clean.

Jason Strong:

I think if we had a tick vaccine that was able to be broadly used and particularly ease of use is a big thing, it would be game-changing, particularly for Northern Australia, but even in other parts of Australia, like the North coast of New South Wales, for example, where there's also challenges with ticks, but being able to treat an animal and being able to know that they were going to be safe from the impact of ticks, being able to move them more easily and know that they were going to actually performance survive would have a big impact on the Australian cattle industry.

Halina Baczkowski:

In Queensland, there are cattle tick zones to manage control. These zones are separated by the tick line. The free zone is where cattle ticks aren't present, the other side is where they are. Professor Tabor's already seeing promising results, which could be good news for producers on the ticky side, helping them save money, time and effort. She's aiming high with her sights set on global success.

What do you hope the end result to be?

Ala Tabor:

A vaccine that will work against cattle tick across the world. Previous vaccines that have been produced have not worked globally and for a company to invest in us, it has to be something that's applicable globally, not just to Australia.

Halina Baczkowski:

Is there an end in sight for you?

Ala Tabor:

I hope so. You're doing it for this long.

ENDS

Media contact: Professor Ala Tabor, Centre for Animal Science, The University of Queensland, E. a.tabor@uq.edu.au or Carolyn Martin, QAAFI comms M: 0439 399 886 E: carolyn.martin@uq.edu.au

Source: ABC TV Landline story Ticked Off: Cracking the code for a cattle tick vaccine, by ABC reporter Halina Baczkowski, ABC TV Landline and broadcast on ABC TV on Sunday 26 July 2020 at 12:30 pm. Watch the full Landline story (7 minutes 46 seconds) from Landline's ABC iView website.