The sorghum story is a strong example of what is possible when there is significant targeted investment in breeding and agronomic research, and a long-term commitment.

When casting around for grains industry success stories, it could be difficult to top the story of sorghum.

Productivity gains in Australian sorghum are the highest in the world, and industry growth is also among the highest, globally, for any cereal crop. In 2015, for the first time, sorghum overtook wheat to become Queensland’s most important cereal crop, with a farm gate value of $432 million.

The Queensland Government initiated the sorghum-breeding program back in 1958 at the Hermitage Research Station near Warwick, and the program began delivering to Australian grain growers through the private seed industry in the mid-1960s.

The GRDC began funding the program in 1993 and in 2010 QAAFI took over the program leadership. Over this period it has evolved to become the most successful public sorghum-breeding program in the world in terms of lines licensed to industry, uptake in commercial varieties and benefits delivered to grain growers.

With a focus on improved yield and climate resilience, commercial licensing of new sorghum lines started in 1989. Since then more than 2400 lines have been licensed, with more than 100 sorghum lines licensed to commercial seed companies in the past year alone.

To put these figures in context, there is more use of the genetic material coming out of the sorghum-breeding program than any other public pre-breeding program in the world.

Germplasm licensed by the program is used directly as hybrid parents and also indirectly, by crossing licensed lines to commercial material to produce new parents within a company’s breeding program.

All Australian hybrid sorghum varieties have genetics from the program, including traits such as midge resistance and staygreen traits (a feature of modern hybrids, which can be traced to program germplasm).

About 90 per cent – or 16 of 18 commercial varieties – are now generating royalties to the core breeding program partners.

One of the challenges for Australia is the small size of the seed market and the potential for companies to introduce parent lines from international programs and not to breed parents under local conditions. This was common from the 1970 to the early 1990s, but from the late-1990s onwards all commercial hybrids contain parents bred in Australia.

The system now encourages companies to continue breeding locally and most hybrids comprise genetics from pre-breeding and from company proprietary genetics, meaning Australian growers get the best of both public and private systems.

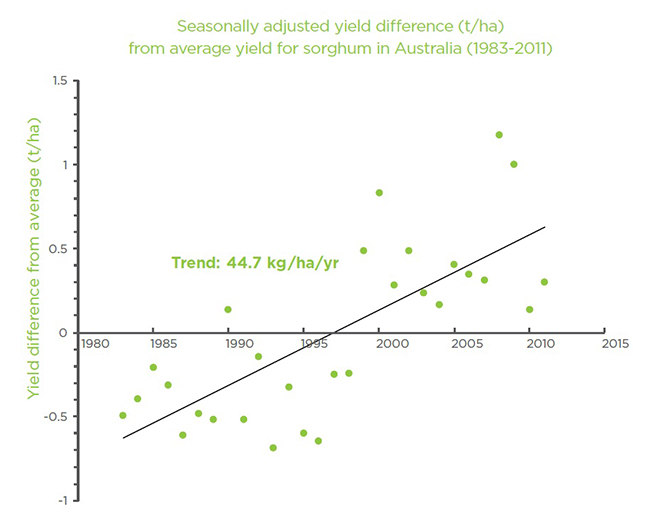

More important from the grower’s perspective, however, is that Australian sorghum has shown productivity gains in the order of three to four per cent per year over the past 20 years, due to the breeding and agronomic improvements that have been achieved. Sorghum now holds the status as one of Queensland’s most valuable agricultural industries.

One of the growers who has seen firsthand the benefit of the research investment is grower Glenn Milne from Dalby, Queensland. Glenn’s family has been hosting breeding trials on his 600-hectare property on Queensland’s Darling Downs since the early 1980s, and he lists midge resistance, standability (reduced lodging) and staygreen as the most important traits the program has delivered.

Australia is currently the only country in the world with midge-resistant sorghum as standard.

“Midge resistance has been the biggest benefit,” he says. “Many people say it’s cheap to spray but the combination of the midge-resistance traits and spray gives you a really robust defence.

“Stay-green also helps in tough conditions, and provides better resistance to Fusarium,” he says.

“There is less lodging among varieties that have the stay-green trait.”

Glenn says climate resilience has improved over the years, which he believes is a result of enhanced genetics and an improved understanding of sorghum agronomy.

“We get better seedset under tough conditions,” Glenn says, “and that is also due to better agronomy. With the introduction of zero-till and knowing how much water the soil can hold, we now understand the right conditions for the plant, so the combination of the breeding and agronomy has pushed productivity up.”

Professor Graeme Hammer, director of the Centre for Plant Science at QAAFI, echoes the grower’s sentiments about the focus on both strands of crop science.

“QAAFI’s strategic research interest in field crop improvement spans genetic improvement as well as agronomic systems,” Professor Hammer says.

“Our big-picture focus is around optimising interactions of genetics and management to get the best out of our variable cropping environment.”

In 2013, the outstanding cumulative results demonstrated by the sorghum improvement program were recognised internationally when the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation awarded the program US$4.6 million (A$6.4 million) to improve breeding programs in Africa, and to map the genes controlling two drought-resistance traits in sorghum.

In 2016, the foundation awarded the team a further US$3.8 million (A$5.3 million) to assess plant-breeding programs in developing countries and identify the best avenues to improve them.

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation program officer Dr Jeff Ehlers said the foundation chose UQ because of its worldwide reputation for excellence in plant breeding, particularly in tropical crops such as sorghum: “Very few organisations have the range of technical expertise and history of success in delivery of improved varieties to farmers as UQ and its partner the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries,” he said.

For geneticist and plant breeder Professor David Jordan, QAAFI’s sorghum team leader, the grants are a testament to the value of long-term investment into high-quality research.

“Australian sorghum’s productivity gains demonstrate the advantages of simultaneously improving both management practices and genetics in an integrated way. It is a long-term investment by both public and private-sector researchers, and if done well, it also generates large returns and lays the foundation for future improvements,” Professor Jordan says.

This project is jointly supported by the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries and UQ, and the GRDC.