If you’ve been paying attention to the controlled environment agriculture (CEA) space over the last decade, you’ve seen the pendulum swing from hype to skepticism, from bold promises to humbled pivots. But few people have lived every angle of this evolution like Professor Paul Gauthier.

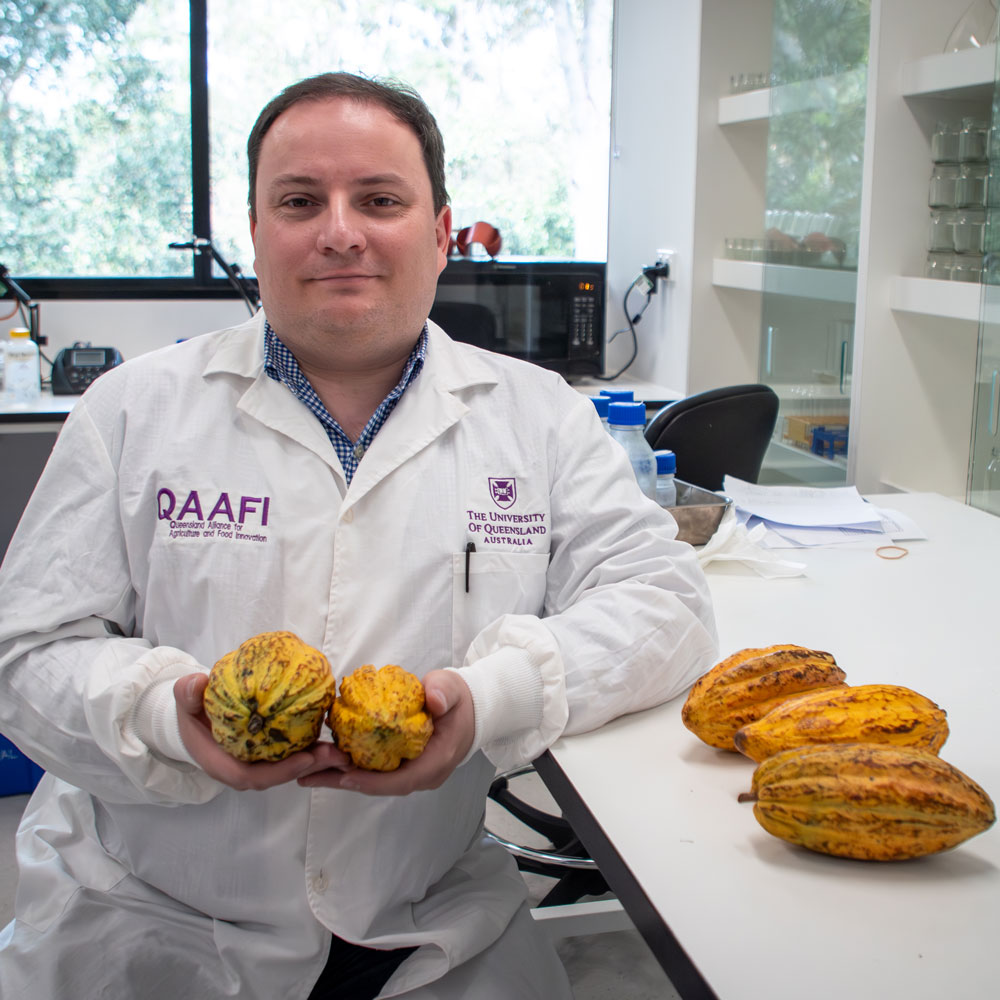

From remote research in northern Sweden to commercial innovation at Bowery Farming, and now academic leadership at the University of Queensland, Paul seems to always have one foot in the lab and one in the grow room. I recently interviewed Paul to get his take on the current state of vertical farming and here are the main takeaways.

Vertical Farming 3.0: The “Neo” Era

According to Prof Gauthier, vertical farming is no longer in its proof-of-concept phase. We’ve crossed that threshold. What comes next isn’t about whether we can grow food indoors—but whether we can do it profitably, reliably, and at scale.

He calls this new phase the Neo-Vertical Farming Industry. And like any “next era,” it comes with new rules of engagement.

“The early days were about feasibility—attracting capital with bold promises and proving we could grow leafy greens indoors. But now, investors are more cautious, consumers are better informed, and isolated pioneers are being replaced by interconnected ecosystems. The question is no longer ‘can we do it?’ but ‘can we make it work—economically?’”

In this emerging era, several outdated assumptions are finally being retired:

Myth #1: Vertical farming will feed the world.

It’s a noble idea, but not a realistic one. The global food system produces billions of tons of food annually. Vertical farming won’t replace field agriculture anytime soon—and it doesn’t need to. Instead, its real value lies in filling gaps: providing high-value crops in urban centres, stabilising supply chains during crises, and delivering fresh produce where climate or logistics make traditional farming unreliable.

Myth #2: Microgreens are the future of food.

Microgreens had their moment as the poster child of indoor farming. But their role is additive, not foundational. They're nutritional garnishes—excellent for enhancing flavour or presentation, but not a primary food source. As Paul puts it, thinking microgreens will revolutionise global nutrition is like thinking foam is the future of cuisine because of molecular gastronomy.

Myth #3: Vertical farming doesn’t work.

Let’s be clear: the technology works. The science is sound. What often fails is the execution. Poor leadership, rushed scaling, and misguided tech investments—not the model itself—are responsible for most of the industry’s high-profile collapses.

Myth #4: Vertical farming is a fast path to riches.

Farming is never a “get-rich-quick” scheme, and vertical farming is no exception. It’s capital-intensive, operationally complex, and deeply dependent on market timing. Profitability is possible—but only with long-term strategy, tight financial management, and a deep respect for the fundamentals of agriculture. Forget the Robots. Focus on Precision and Simplicity.

Why Complexity ≠ Innovation: Rethinking Automation and AI in Vertical Farming

In today’s race to differentiate, too many vertical farming startups are chasing the flashiest tech. Fully automated systems, robotic pickers, conveyorised growth modules—it all looks impressive in a pitch deck. But as Professor Gauthier points out, complexity often masquerades as innovation.

“We’ve overengineered our way into fragility,” he says. “Vertical farms don’t fail because the lights are wrong—they fail because their systems are too rigid, too costly, and too difficult to manage in real-world conditions.”

Instead of layering on more automation, Paul advocates for a lean, precise, and disciplined approach. One where every technology investment is judged not by its novelty, but by its contribution to consistency, cost-efficiency, and crop quality.

His core advice?

- Avoid unnecessary automation. Don’t replace people just because you can. In many cases, a well-trained grower will outperform a robot—especially in nuanced tasks like pest scouting, pruning, or diagnosing subtle plant stress signals. Automation should serve proven processes, not attempt to replace them before those processes are fully understood.

- Prioritise crop specialisation. Trying to grow “everything, everywhere” is a recipe for operational chaos. Instead, build systems around a narrow set of high-value crops with regional relevance—those that solve real market problems and suit the infrastructure you’ve built.

- Pursue operational excellence before technological flash. Get the basics right first: irrigation, lighting, climate control, workflow design. Streamlined, repeatable operations beat flashy, brittle systems every time.

While Paul is cautious about over-automation, he’s bullish on AI—but only if it’s positioned correctly. AI isn’t a grower replacement; it’s a decision-making ally.

“AI can help manage complexity, detect issues earlier, and deliver consistency in ways humans alone can’t. But it only works when it’s built on good data, strong agronomy, and clear operational goals.”

In particular, AI shines in:

- Real-time environmental monitoring and automated alerts.

- Predictive analytics for disease risk and growth rates.

- Pattern recognition across R&D trials, enabling faster iteration.

- Adaptive control systems that fine-tune conditions on a crop-specific basis.

As we enter the era of precision plant growth—where we tweak light spectra, nutrient formulations, and airflow dynamics based on a crop’s genetic profile—AI becomes the bridge between biological complexity and commercial viability.

The takeaway? Technology should be a tool, not a trophy. The most successful vertical farms of the future won’t be the ones with the most robots. They’ll be the ones that know exactly which technologies to use, when, and why—and combine them with smart people, tight systems, and an obsession with growing the best crops for the right markets.

The Homegrown Innovation Challenge: A Model Worth Scaling

Both Paul and I are judges for the Homegrown Innovation Challenge, which will announce its latest round of winners on June 3rd. So, I wanted to ask about Paul’s experience as a judge for the Challenge. For Paul, it has reinforced what he’s long believed: Focused funding with structure and accountability delivers real impact.

"The teams we evaluated with innovative, highly motivated, and deeply understood the urgency of Canada's berry industry limitations. I hope more initiatives like this emerge to drive targeted solutions rather than reinventing the wheel.

“We need more of these outcome-driven initiatives—deep focus, real support, and site-based evaluation.”

The standout theme? Teams that grasped the systemic issues—like the lack of disease-free strawberry plant material—offered the most viable solutions. Not coincidentally, they were also the most collaborative.

Re-centre the “Farming” in Vertical Farming

In Paul’s words, one of the sector’s biggest missteps is conflating farming with solutions development. The industry’s true purpose is being obscured.

“Vertical farming should be an enabling platform—not a silver bullet. Innovators should support farmers, not replace them.”

He also advocates for more openness in the industry. Crop recipes and growing protocols shouldn’t be hoarded under the guise of IP. Much of this is based on public research. Collaboration will be the industry’s competitive edge.

Final Takeaway

Professor Gauthier’s north star is clear: systems that integrate science, business, and engineering, all centered around the crop—not the tech stack.

So, if you’re building in this space, ask yourself:

- Are you solving a real problem?

- Are you keeping it simple?

- Are you growing with integrity?

The future of vertical farming depends not just on innovation, but on humility, collaboration, and grounded strategy.

As Paul reminds us:

“Grow slow but steady—that’s how farming is done right.”

Contact: Professor Paul Gauthier, p.gauthier@uq.edu.au, QAAFI Communications, Natalie MacGregor, n.macgregor@uq.edu.au, +61 409 135 651.

The Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation is a research institute at The University of Queensland, established with and supported by the Department of Primary Industries.

Republished with permission.